Chamber Singers host Q&A with Lyric Opera of Chicago prompter

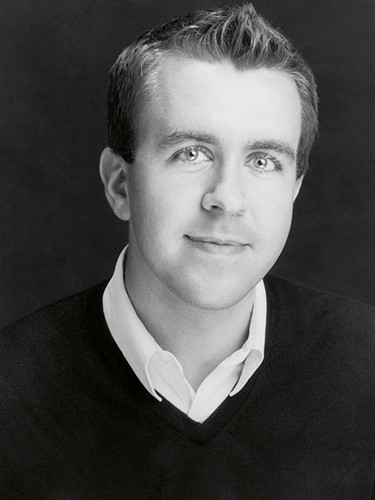

As an opera prompter, Matthew Piatt works with each singer individually to help them perfect their roles in the production. The prompter also acts as an assistant conductor, guiding the performers through the music so they can focus more on their acting and technique. This means that Piatt must have every singer’s part committed to memory before the first day of rehearsal.

In order to finish out their spring semester, the Chamber Singers voted to watch and analyze Richard Wagner’s “Der Ring des Nibelungen,”also known as “The Ring Cycle.” “The Ring Cycle” is a series of four German operas loosely based on Norse mythology and the ancient German epic, the “Nibelungenlied.”

The plot of “The Ring Cycle” will later heavily influence what we know today as “The Lord of the Rings” series.

With the complete story totaling about 15 to 18 hours of music, depending on the conductor, “The Ring Cycle” is such a large and expensive production that it is only performed live in its entirety every five to 10 years.

The Chamber Singers held a Zoom Q&A on May 1 with Matthew Piatt, who is in his seventh season as an assistant conductor and prompter for the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

If not for COVID-19, Piatt would be preparing for his third live run of “The Ring Cycle.”

Piatt is originally from Victoria and attended high school at Thomas More Prep-Marian. He later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Houston with a bachelor’s degree in piano, going on to receive his master’s in collaborative piano at the University of Michigan, where he studied with Martin Katz.

For more on Piatt’s professional achievements, check out his music staff bio on the Lyric Opera of Chicago website.

Q: “Who or what in your life inspired you to gravitate towards a career in music?” – sophomore Samantha Vesper

A: “I come from a musical family and still have vivid childhood memories of my great aunt Dorothy, who was a very talented pianist and organist,” Piatt said. “When I was little, we used to visit her in the nursing home. We could wheel her chair up to a piano, and she could sit there and play remarkably well for great lengths of time. It was something that always inspired me, and I was eager to start piano lessons as early as possible. My first teacher, the wonderful Leona Schulte of Victoria, was a fantastic early influence on me. I loved her tough, no-nonsense approach, and not until I grew older did I fully appreciate everything she had taught me while I was still young. She was the first of a long line of fantastic teachers in my life — each of them inspiring and demanding in different ways. Even as a professional musician, I am still fortunate to encounter very inspiring conductors, singers and instrumentalists who set fine examples and make me want to improve my own skills.”

Q: What are some of the most difficult aspects of opera prompting?” – senior Sierra Adkins

A: “Ideally, you need to be well-versed in three to five foreign languages,” Piatt said. “I have prompted in German, Italian, French, Russian and Czech. I don’t speak all of those fluently, but I have to have enough familiarity with the language that I sound sufficiently ‘convincing.’ It’s very intimidating to prompt Russian singers in Russian, but generally those people tend to be very appreciative that you have tried hard to learn their language. In an ideal world, I try to have as much of an opera memorized as possible, meaning that for a three- or four-hour-long opera, I aim to be able to sing most of the parts perfectly without looking at the music. That involves an enormous amount of practice and repetition, usually something I do unpaid for months before any rehearsals begin. Once you have gotten that much self-preparation under your belt, it then becomes a matter of collaborating with all the different personalities in a cast. Some people want you to be very hands-on, while others might find you distracting and prefer you leave them alone. It’s always a delicate balancing act – in scenes that involve many singers, you have to memorize things like ‘The soprano wants this line prompted this way, the tenor wants nothing, and the baritone wants a cue, but only if he looks at me one measure beforehand.’ Your brain has to be able to think both in time with the music and also one or two measures ahead, so it can be surprisingly easy to get lost if you’re not careful.”

Q: “What kind of time period would you need to rehearse for ‘The Ring Cycle,’ with it being such a complex production?” – junior Andrew Duke

A: “For more difficult productions, most companies plan for four or five weeks of rehearsal,” Piatt said. “A normal workday for me involves six hours of rehearsal, and we always work six days per week, with only one day off. That usually involves approximately 36 hours of rehearsal per week. When we produce an opera that is less musically complicated, three weeks tends to be the normal length for a rehearsal process. Amazingly, there are a lot of companies, especially in Europe, that produce so much opera that they are able to throw a show together in just a few very hectic days, but that is very rare in the United States.”

Q: “How frustrating is rehearsing ‘The Ring Cycle,’ and how rewarding are the performances?” – sophomore Sydney Wittkorn

A: “[Frustration] is a very real issue that we all face on a daily basis,” Piatt said. “A lot of us professional musicians are real perfectionists and hold ourselves to very high standards at all times. That means that when things go even slightly awry, the energy in a rehearsal room can become tense, and it is often because a great artist is getting very frustrated at himself or herself. I personally feel that part of my job is to help everyone do his or her best work, which means that I am constantly changing the way I prompt someone to see if a new tactic has a better result. Instead of walking up to a singer and saying, ‘In the last scene, you made 12 mistakes, and here they are, one by one…,’ I try to remember what they did wrong and try to preempt those mistakes the next time. For instance, if someone always wants to come in early at a certain point, I will hold out my hands aggressively to say ‘Stop!’ whenever we get back to that same moment. If they happen to look at me around that time, they will see that I am using nonverbal cues to ‘retrain’ their instincts. Since rehearsal time always feels limited for the amount of work that needs to be done, these sorts of nonverbal signals can really save a lot of time and ultimately means that the singers can worry more about their acting and technique as opposed to feeling insecure musically. Anyway, this process involves a lot of trial and error, and sometimes it takes a while before you feel ‘in sync’ with a new singer. That can come with a fair amount of frustrations, but in almost every production, by the time we open a show, I feel very gratified that the work I put in has paid off. There is a very specific thrill that comes with prompting a live performance, and every time I feel that, I remind myself that even the most stressful rehearsal periods were worth the effort.”

Q: “What advice could you give for students looking to go after their own careers in music?” – junior Zach Chance

A: For anyone interested in pursuing music, I would say that you need to be prepared to put in an enormous amount of work,” Piatt said. “Obviously, the act of performing music has many therapeutic benefits and can seem like a pastime or leisure activity to anyone who studies music for fun. But pursuing a music degree involves an enormous amount of discipline and non-glamorous work that is, of course, true of almost any profession. You need to be prepared to spend hundreds, if not thousands, of hours in practice rooms, early in the morning or late at night, and for most of us, it can feel like your work is never done. Even as someone who has a lot of experience under my belt, whenever I start to learn a new opera, I know that means I’m looking at maybe 100 to 200 hours of unpaid, hard work, just to feel that I am adequately prepared by the first day of rehearsal. It is not a field in which you suddenly achieve a certain milestone, and you have ‘arrived.’ It is constant work, and it is not for everyone.”

“However, beyond the work aspect of it, I personally would encourage you to explore other fields of study if you are pursuing a music degree. In my undergraduate studies at the University of Houston, I had to take courses in human civilization, psychology, geology, etc. At the time, it felt like those things were often taking away from my practicing and musical training, but in retrospect, I am so thankful to have received a more general education. One thing I didn’t do is study business in any capacity, and I wish that was something I had thought to pursue when I was younger. Being a musician definitely involves a lot of business savvy, and in my own experience, this was not addressed very much in the colleges I attended. Figuring out how to run your own business, negotiate taxes, or set a budget are all very important skills too.”

“Finally, if you choose to pursue an education in music, never forget your sense of identity and what personally inspires you about music,” Piatt said. “Collegiate-level music training is often very demanding and requires you to develop many skills you may lack altogether or have previously ignored for some reason. And as your professors push you to become the best version of yourself, it is easy to lose your sense of self. You will never stop comparing yourself to others around you – people who are more or less talented in various ways – and we are all sensitive people at the end of the day. It can be very discouraging when you see others excelling at things that don’t come naturally to you. You may also perceive that people who don’t seem to work as hard seem to get more opportunities and recognition, even though you may not personally respect their workmanship. No matter what, you have to maintain your own integrity and trust what you have been taught by respected teachers and mentors. In my career, the people who inspire me the most are those who project modesty and humility and seem to be in the profession for their love of music itself as opposed to self-promotion. There will be stressful moments, but if you can remind yourself of the merits of studying music for music’s sake, the happier and more successful you will be.”

21cleiker@usd489.com

Caitlin Leiker is a senior, and this is her third year in newspaper. She is involved in Chamber Singers, Musical, Spring Play, National Honor Society,...

![English teacher Vanessa Schumacher likes to decorate her classroom for Christmas along with her house. Her school decorations are complete with a mini tree, as well as festive garland and lights hung around her room. “Every year I bring [the tree] on Nov. 1, or right after Halloween,” Schumacher said. “I bring it just to be funny.”](https://hayshighguidon.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Christmas-Decorating-Schumacher-Tree-242x475.jpg)